Curated by Violette Morisseau

The ‘cocoon’ sculptures on which the exhibition opens, suspended or hung, seem like outgrowths of the walls. They have the dual effect of being able to carry and protect a body –either human, mineral or plant – against itself. Skin-to-skin contact creates a symbiotic relationship: the wearer’s body is instinctively covered in scales, adorned with coppery and undulating exoskeletons. In a form of transference, through the contact of the skins, a little of one passes into the body of the other.

As we descend the stairs, Orion’s babbling begins to be heard. At his age, he has the ability to identify and memorise an infinite number of sounds, from every mouth and every culture. Although this skill fades with time and situated learning, these vocalisations are those of a universal song, potentially containing all the languages of the world.

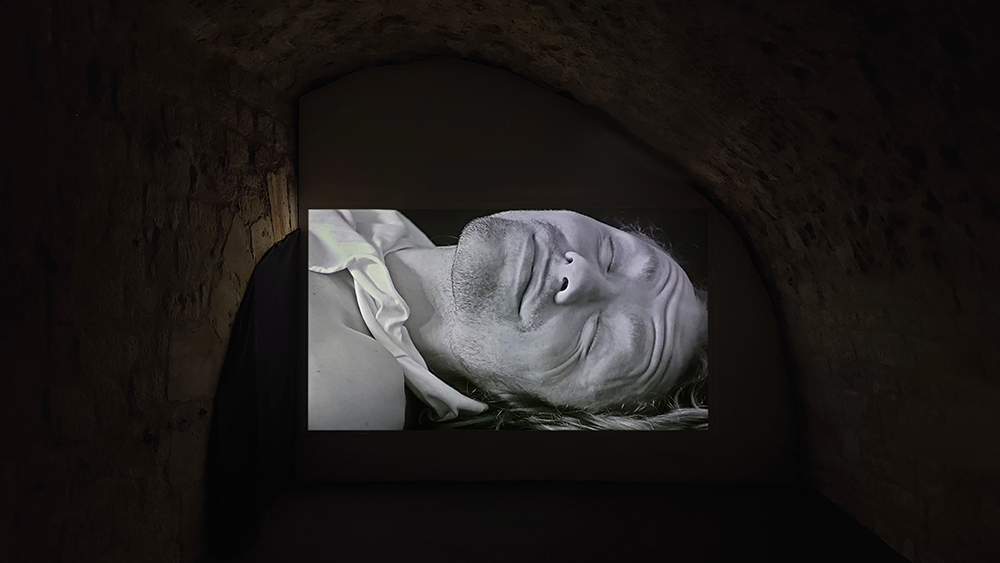

With new-borns, the integration of knowledge is inseparable from moments of sleep: it is during the first phase of sleep, which is often agitated, that the new information gathered during the periods of wakefulness is processed and memorised. This is when a universal phenomenon occurs: the infant’s face displays a succession of innate emotions: joy, surprise, fear, disgust, sadness and anger. Its body moves in sudden, jerky movements, with limbs twitching and relaxing. You observed this sort of spasmodic dance in Orion, and asked the choreographer Theo Pendle to interpret it. Lying on his back, an unsuspended horizon of movement opens up to the dancer: from micro-gestures to convulsions, this is the dance of a body that memorises the world.

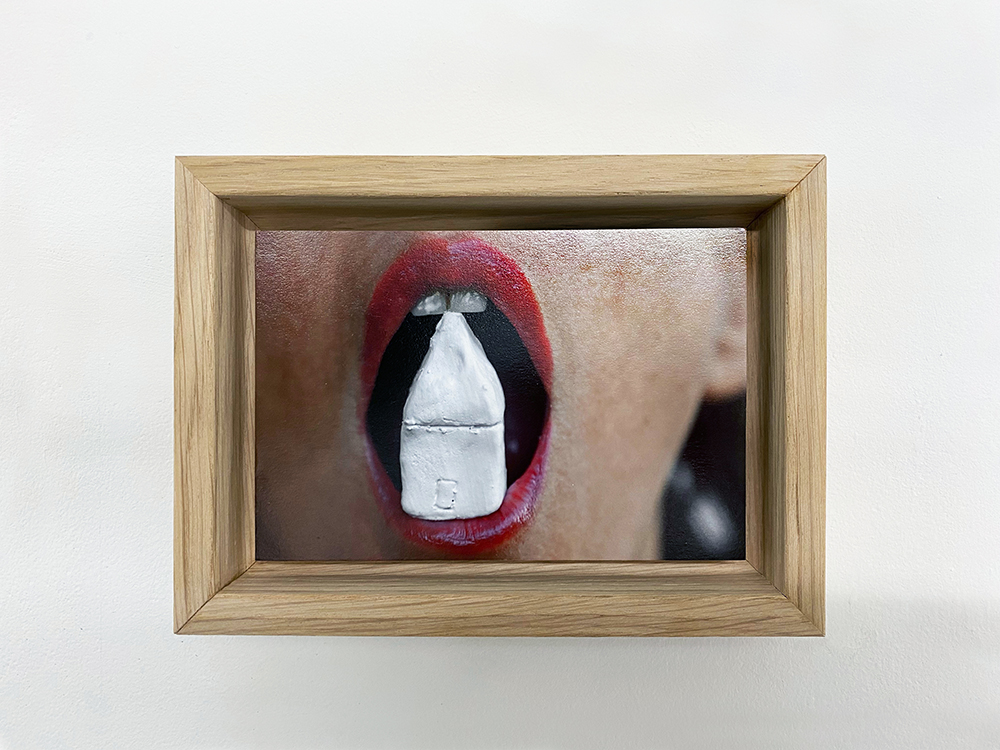

In the adjoining room, a soft space where bodies can move without injury, you’ve hung a number of sculptures, remarkable for their haptic qualities. These are works to be looked at lying on your back, to be touched, sculptures to be bitten. Here you return to your lifelong obsession with transitional objects, defined by Winnicott as essential supports for the child’s emotional projections. These objects help them to become aware of their individuality and to see others as the outside world rather than parts of themselves.

You, whose practice constantly tests the elasticity of the distances between individuals in order to reposition them in the world, have decided to put us in the place of a new-born baby. A soft, cuddly world, where things are understood with the mouth. Orion tenderly shows us the way to swallowing the world and assimilating it.

Cocoon (Dragonfly), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather silver color, fabric, 180 x 70 x 30 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Sardine), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather turquoise color, fabric,

125 x 60 x 100 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Ornithorynque), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather beige color, fabric,

105 x 60 x 15 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Ladybug), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather red color, fabric, 85 x 50 x 35 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Dragonfly), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather silver color, fabric, 180 x 70 x 30 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Dragonfly), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather silver color, fabric, 180 x 70 x 30 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (Ear), 2023, Digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame),

19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

The World in My Mouth (Ear), 2023, Digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame),

19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocoon (Sardine), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather turquoise color, fabric,

125 x 60 x 100 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Ornithorynque), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather beige color, fabric,

105 x 60 x 15 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (Crouching Caryatid), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame),

19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocon (Ladybug), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather red color, fabric, 85 x 50 x 35 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Ornithorynque), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather beige color, fabric,

105 x 60 x 15 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (Crouching Caryatid), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame),

19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocoon (Ladybug), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather red color, fabric, 85 x 50 x 35 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Ornithorynque), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather beige color, fabric, 105 x 60 x 15 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (Crouching Caryatid), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame), 19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

The World in My Mouth (Crouching Caryatid), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame),

19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocon (Ladybug), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather red color, fabric, 85 x 50 x 35 cm around, unique piece

Cocon (Ladybug), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather red color, fabric, 85 x 50 x 35 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (Finger), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak oater frame, 10 x 15 cm (without frame),

14 x 19 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocoon (Dragonfly), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather silver color, fabric, 180 x 70 x 30 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (Ear), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame),

19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocoon (Sardine), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather turquoise color, fabric,

125 x 60 x 100 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (Finger), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 10 x 15 cm (without frame),

14 x 19 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocon (Ladybug), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather red color, fabric, 85 x 50 x 35 cm around, unique piece

Cocoon (Beetle), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather kaki color, fabric, 190 x 80 x 25 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (House), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium,

oak floater frame, 10 x 15 cm (without frame), 14 x 19 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

The World in My Mouth (Venus), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium,

oak floater frame, 25 x 16,5 cm (without frame), 29 x 20,5 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Cocoon (Beetle), 2023, sculpture, recycled leather kaki color, fabric, 190 x 80 x 25 cm around, unique piece

The World in My Mouth (House), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 10 x 15 cm (without frame),

14 x 19 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

The World in My Mouth (House), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium,

oak floater frame, 10 x 15 cm (without frame), 14 x 19 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

The World in My Mouth (Venus), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 25 x 16,5 cm (without frame),

29 x 20,5 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

The World in My Mouth (Eye), 2023, digital color, photography couleur inkjet printed on Epson Baryta paper, glued on 1mm aluminium, oak floater frame, 15 x 10 cm (without frame),

19 x 14 cm (with frame), edition of 3 + 2 AP

Teethers, 2023, 62 polymer clay sculptures, plaster, varnish, threads, fabric cushions, variable dimensions, unique pieces. Red light installation. Soundtrack installation, loop, 11’26’, edition of 3 + 2 AP

Teethers, 2023, 62 polymer clay sculptures, plaster, varnish, threads, fabric cushions, variable dimensions, unique pieces. Red light installation. Soundtrack installation, loop, 11’26’, edition of 3 + 2 AP

Teethers, 2023, 62 polymer clay sculptures, plaster, varnish, threads, fabric cushions, variable dimensions, unique pieces. Red light installation. Soundtrack installation, loop, 11’26’, edition of 3 + 2 AP

Orion’s first dance, 2023, HD video, black and white, sound, 10’37’’, edition of 5 + 2 AP. With the participation of the choreographer Théo Pendle.

Thanks to Violette Morisseau, Galerie Dohyang Lee, Orion Ceraudo Papadimouli, Vincent Ceraudo, Victoria Frenak

Orion’s first dance, 2023, HD video, black and white, sound, 10’37’’, edition of 5 + 2 AP. With the participation of the choreographer Théo Pendle.

Thanks to Violette Morisseau, Galerie Dohyang Lee, Orion Ceraudo Papadimouli, Vincent Ceraudo, Victoria Frenak

View of the exhibition The World in My Mouth

73-75 rue Quincampoix 75003 Paris France

Tuesday – Saturday 2 pm – 7 pm and with rendez vous

tel : +33 (0)1 42 77 05 97

www.galeriedohyanglee.com